Top Ed-Tech Trends of 2016

A Hack Education Project

Education Technology and the Promise of "Free" and "Open"

This is part four of my annual review of the year in ed-tech

The Rebranding of MOOCs

Remember 2012, “The Year of the MOOC?”

Remember in 2012 when Udacity co-founder Sebastian Thrun predicted that in fifty years, “there will be only 10 institutions in the world delivering higher education and Udacity has a shot at being one of them”?

Remember in 2012 when edX head Anant Agarwal predicted that “a year from now, campuses will give credit for people with edX certificates”?

Remember in 2012 when Coursera co-founder Daphne Koller said in her TED Talk that her company’s goal was to “take the best courses from the best instructors at the best universities and provide it to everyone around the world for free”?

Remember in 2012 when the media wrote about MOOCs with such frenzy, parroting all these marketing claims and more and predicting that MOOCs were poised to “end the era of expensive higher education”?

Remember? Or, with its penchant for amnesia, has education technology already forgotten?

MOOCs were, for a year or two at least, able to dominate conversations about the future of education and the future of education technology, often invoking the words “free” and “open” as a rallying cry against institutions and practices that were, in contrast, “expensive” and “closed.” But now it seems as though most – although certainly not all – of the hype has died down. Along the way, most of the predictions and promises have been broken:

Attending a MOOC now often costs money; receiving a certificate certainly costs money. Coursera began charging for certificates in January and launched a subscription service in October. In January, Udacity unveiled the “Nanodegree Plus,” a $299/month nanodegree that comes with “a money-back guarantee.” edX’s “Introduction to Philosophy” course began in September, with a $300 fee in order to have an MIT grad student grade one’s work.

MOOCs are not particularly "open." The sustainability of these courses – including the persistence of students’ own work – is precarious at best, as Coursera students discovered when the company informed them it would remove hundreds of old courses, along with their access to their coursework, from its site.

The founders of the most well-known MOOC startups have largely “have abandoned ship,” as historian Jonathan Rees put it. Daphne Koller announced her departure from Coursera in August; she’s now working for Alphabet (a.k.a. Google)’s biotech company, Calico. (Andrew Ng, left the startup several years ago to join the Chinese search engine Baidu.) And Sebastian Thrun, who founded the rival Udacity, left that startup and is rumored to be back in the self-driving car business.

Several faculty who participated in early MOOC experiments now say they were casualties of the “gold rush.” Many MOOC instructors continue to insist they “need more support.”

Enrollments in many MOOC programs were not as high as hoped (or as budgeted). The cost of developing courses, for universities, remains incredibly high – $350,000 for each course that was part of the Georgia Tech and Udacity partnership, for example.

“Democratizing college,” it turns out, is hard work.

And today most MOOC companies have pivoted away from that to offer corporate training, professional development, and job placement services instead. Coursera launched “Coursera for Business” in August, for example, just a few weeks after Koller announced her departure from the company.

So “MOOCs Are Dead,” Mindwire Consulting’s Phil Hill pronounced. “Long Live Online Higher Education.”

I’m sure MOOC proponents would love to take credit for a legitimization of online higher education, as if the history of online higher education began at Stanford or MIT in 2012.

According to the Babson Survey Research Group, which released the last of its annual surveys of online education this year, “more than one in four students (28%) now take at least one distance education course (a total of 5,828,826 students, a year-to-year increase of 217,275).” But while universities might be more accepting of online education, the Babson Survey also found that the number of chief academic leaders who say that online education is critical to their schools’ long-term strategy actually fell this year – from 70.8% last year to 63.3% this year. For their part, many faculty remain skeptical of online education. And many students – in high school, in community college, and at the university level – still say they prefer face-to-face classes, particularly when the course material is interesting or challenging.

The core promise of MOOCs, remember, was to “democratize access,” increase affordability, and as such to allow people all over the world to experience the benefits of formal education, even if informally. “Online Delivery Increases Pipeline of Students Pursuing Formal Education,” Edsurge pronounced in October, describing an NBER working paper. An amazing discovery by researchers: expanding enrollment options found to expand potential enrollments.

(And indeed, if nothing else, MOOCs have remained a popular subject for education researchers.)

But another NBER research paper underscores how little MOOCs specifically and online education more broadly have moved the needle on college affordability, again despite all those proclamations that MOOCs specifically and ed-tech more broadly would solve higher ed’s “cost disease.” (A sidenote: RIP William Bowen, who defined this problem of productivity with William Baumol and who passed away this year.) “A federal rule change that opened the door to more fully online degree programs has not made college tuition more affordable.” (emphasis mine)

Perhaps, in the end, “MOOCs were much more the signifier of sociocultural phenomenon than they were an educational salvation,” as Seattle Pacific University’s Rolin Moe has argued.

Because MOOCs have now largely pivoted to corporate training and because they continue to push for alternative credentialing (rather than simply for MOOCs for college credit), I will – sadly – have to talk about MOOCs again in subsequent articles in this series.

Financial data for Coursera, Udacity, edX, and other MOOC-related companies, along with the list of MOOCs’ new academic partners, can be found on funding.hackeducation.com.

The College Affordability Crisis

“From January 2006 to July 2016,” wrote the Bureau of Labor Statistics in August, “the Consumer Price Index for college tuition and fees increased 63 percent, compared with an increase of 21 percent for all items.” ProPublica, also writing in August, observed that “from 2000 to 2014, the average cost of in-state tuition and fees for public colleges in America rose 80 percent. During that same time period, the median American household income dropped by 7 percent.” Tuition keeps going up and up and up, although as The Wall Street Journal noted this fall, published tuition rates only rose 2.4% during the 2016–17 academic year, “slowing from 2.9% last year.”

Growth could slow to zero, and tuition would still be out-of-reach for many, many students.

(Highly recommended: Temple University’s Sara Goldrick Rab’s 2016 book Paying the Price: College Costs, Financial Aid, and the Bretrayal of the American Dream.)

To blame for the soaring cost of college? Pick your culprit to confirm your bias: Bloated administration or luxury dorms or climbing walls and other student amenities or tenured faculty salaries or the reduction in public funding or the growth in student aid.

According to the Delta Cost Project, which tracks college spending, spending has increased across all types of college. The spending at public four-year colleges and universities rose, on average, by 2 to 3%, “the largest such increase since the start of the recession in 2008.” Operating costs are no longer being shifted onto students, but as the Delta Cost Project points out, “tuition revenue still financed a majority of education-related spending at public and private four-year institutions,” covering about 63% of educational costs (up from 50% in 2008).

Again, even as things get a little better, they’re still really bad.

Data on government funding for education can be found on funding.hackeducation.com.

State support for higher education was up 4.1% this year, according to the annual Grapevine Report – 39 states reported an increase and 9 reported a decrease in funding. But it’s worth noting that funding varied widely from state to state and that that increase in spending does not mean that per pupil spending has also risen, particularly as enrollment figures change. Another report – this one from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities – claimed that “states are collectively investing 17 percent less in their public colleges and universities, or $1,525 less per student, since 2007.”

The system for funding American flagship public universities is “gradually breaking down,” Robert J. Birgeneau, a former chancellor of the University of California, Berkeley, cautioned. Many institutions face financial difficulties – laying off staff and faculty – and in July The Wall Street Journal reported that some five hundred schools are on the Department of Education’s financial watchlist. “Public universities have ‘really lost our focus’,” says UC Santa Barbara professor Chris Newfield, who also published a book this year on the future of higher education: The Great Mistake: How We Wrecked Public Universities and How We Can Fix Them.

Meanwhile, donations to various capital campaigns for sports facilities and aid to student athletes clocked in at over $1.2 billion. Go team.

According to a report released this fall by the Commission on the Future of Undergraduate Education, “More Americans are attending college than ever before – nearly 90 percent of millennials who graduate from high school attend college within eight years.” But attendance does not equal completion, and one of the major reasons that students do not finish their education: finances.

Students’ financial situations are precarious, and this exacerbates the growing – unmanageable – cost of college attendance. According to a report from the Wisconsin HOPE Lab,

Three in four undergraduates defy traditional stereotypes. Just 13% live on college campuses, and nearly half attend community colleges. One in four students is a parent, juggling childcare responsibilities with class assignments. About 75% work for pay while in school, including significant number of full-time workers. The number of students qualified for the federal Pell Grant – a proxy for low-income status – grew from about 6 million in 2007–2008 to about 8.5 million in 2013–14. This is unsurprising given that participation in the [National School Lunch Program] grew by 3.7 million students during that With more than one in five children living in poverty, college-going rates at a national high, and the price of higher education continuing to rise, food insecurity among undergraduates is probably more common than ever.

The National Student Campaign Against Hunger and Homeless found that 48% of college students reported food insecurity in the last 30 days, something far more prevalent for students of color. Indeed, contrary to the stereotypes about providing luxury dorms, many colleges are now starting to provide food pantries for hungry students and their families.

Data “Solutionism” and the College Scorecard

In the light of these figures, the Department of Education’s effort to address affordability through its College Scorecard feels rather pathetic. In an interview with The Chronicle of Higher Education this summer, the Under Secretary of Education Ted Mitchell (formerly a venture capitalist at NewSchools Venture Fund) claimed that the scorecard was one of the “greatest victories” for the Obama administration. When questioned by CHE’s Goldie Blumenstyk about whether or not the scorecard addresses schools’ accountability in the affordability crisis, Mitchell says,

The kind of accountability that matters on the ground is the kind of accountability that allows an individual user to identify what’s important to them, to get reliable information about that, and then to make decisions about it.

In other words, the burden is on students, on individuals, not on schools or government systems and structure – a reflection, as I’ve argued again and again, of the Silicon Valley ideology and its neoliberal, individualist approach to education.

Mindwire Consulting’s Phil Hill has repeatedly pointed out that the data that informs the scorecard is limited and flawed. But even with new and improved data, it’s this underlying assumption by Mitchell that is perhaps most troubling: college affordability is simply about individual consumers making the “right” choice.

So who does the College Scoreboard really serve? According to a study conducted by College Board researchers, “The subgroups of students expected to enter the college-search process with the most information and most cultural capital are exactly the students who responded most strongly to the Scorecard.” Cultural capital and financial capital – these help explain why wealthy students are still much more likely to receive a Bachelor’s Degree.

The Promise of “Free College”

“Free college” was an issue in the US Presidential Election this year, thanks in no small part to Senator Bernie Sanders, who made “tuition free and debt free” college a cornerstone of his campaign. Both Hillary Clinton and the Democratic Party adopted some of Sanders’ language, proposing free, in-state public college tuition for those with incomes up to $125,000.

Free community college has also been an initiative supported by Second Lady Jill Biden, a community college instructor herself.

After Clinton’s defeat, The Washington Post asked, “Did the idea of free public higher education go down with the Democrats?” But “free college” hasn’t been the purview solely of Democrats, and much has happened at the state and local level to try to move this direction.

The Detroit Promise Zone program, for example, which launched in March, would make community college in the city free for its graduating high school seniors. Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti, in his April “State of the City” speech, committed to “giving every hardworking graduate of the Los Angeles Unified School District one free year of community college.” San Francisco Board of Supervisor member Jane Kim also proposed eliminating tuition at the City College of San Francisco for the city’s residents. The state of Washington plans to pilot a program that would cover the cost of degree completion for students who are fifteen or fewer credits away from graduation – “free to finish.”

There were setbacks, however, in the push for free college (beyond, of course, the election of Donald Trump and a Republican Senate and House of Representatives): Kentucky’s governor Matt Bevin vetoed a bill that would have given free community college to students in the state. And while the state of Oregon launched its free community college program this fall, several college leaders in the state said that they thought the program was “underfunded and too exclusive.”

So, “who pays” and “who benefits” from free college remain unresolved issues (along with a slew of other potential and imagined problems).

Some individual schools did take steps to make tuition free or deeply discounted, in part by seeking financial support from private businesses and organizations. Portland State University, for example, said it would offer four years of free tuition to qualifying students. In North Carolina, Elizabeth City State University, UNC Pembroke, and Western Carolina University said they would begin offering $500 in-state tuition starting in fall 2018. Stanford said it would pay for the MBA of students – provided they go work in an “underserved region.” (That region, what journalist Sarah Kendzior calls “flyover country”: Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, or Wisconsin. Keep flying, Stanford MBAs. Please.)

Harvard also opted to use its $38 billion endowment to make its tuition free. Hahahahahaha. Who am I kidding? Harvard wouldn’t even pay its food services workers the $35,000 salary they demanded, prompting them to strike this fall.

In other news, the University of Cambridge plans to offer a $332,000 doctorate degree.

The Market for Student Loans

The topic of student loans could probably be its own article in this series, and I have written again and again and again this year that we need to be paying much closer attention to investor interest in the private student loan market. This is the most well-funded subsection of ed-tech (although it’s rarely discussed by most ed-tech publications, who dismiss it as “financial tech”). But I’m including loans here not only because the burden of student of loan debt is helping spur conversations about college affordability. I want to point out that education technology investment is not interested in “free and open” when it comes to higher education. It is interested in new markets to profit from. And the private student loan market and Wall Street, particularly under President Trump, are now very well positioned to do just that.

Investment data for private loan companies can be found on funding.hackeducation.com.

From 2007 to 2015, total outstanding federal student loan debt doubled from $516 billion to $1.2 trillion, according to the U.S. Department of Education, with individuals who borrowed money for school owing, on average, over $30,000.

According to an SEC filing, student loan provider Navient reported that delinquency rates reached their lowest levels this year since 2005 for the Federal Family Education Loan Program and for private education loans. The Department of Education echoed that data, announcing in September that “the three-year federal student loan cohort default rate dropped from 11.8 percent to 11.3 percent for students who entered repayment between fiscal years 2012 and 2013” – the lowest default rate in three years. Nonetheless, as Wall Street Journal reported in April, more than 40% of student borrowers are not making their loan repayments. (Some of that, in all fairness, is due to deferment.)

The interest rates on student loans are poised to drop again for the 2016–2017 academic year – but that is, let’s remember, for federal student loans, which (for now) constitute about 90% of all loans taken to pay for school. (Credit card debt, which is often used to pay for tuition, textbooks, and living expenses, does not count towards this statistic.)

The burden of student loan debt falls disproportionately on Black students, as student loan disbursement, student loan collection, and job opportunities are racially biased. (This is a topic I will explore more in the final article in this series on education, education technology, and “discrimination by design.”) A study published in the journal Race and Social Problems found “that black young adults have 68.2 percent more student loan debt, on average, than do white young adults.” This debt also connected to the rates at which Black students enroll in for-profit higher education – again, another topic for a subsequent article in this series.

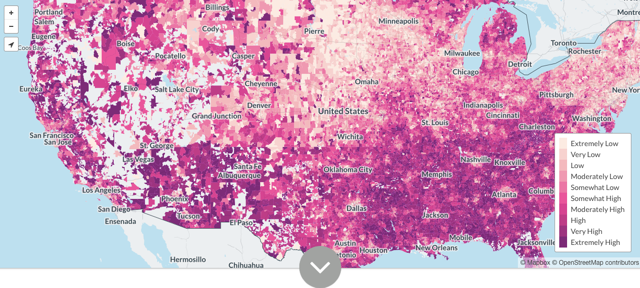

Image credits: Mapping Student Debt

In February, a news station in Houston reported that “US Marshals arresting people for not paying their federal student loans.” The story quickly went viral, and although authorities insisted that the video footage of armed agents at someone’s door was “not what it seems.” But the story’s popularity probably underscores the fear and uncertainty that people do live in because of their debt. Those with student loan debt report higher rates of stress and lower wealth. They may be reluctant to enter into relationships (and people are reluctant to enter into relationships with borrowers in turn). They may be more reluctant to start businesses or buy houses. Reluctant or unable.

The problem with student loan debt isn’t simply it’s amount or the burden that it places on borrowers individually or the economy as a whole. It’s that many students who take loans do not graduate. They have debt but no degree.

Nevertheless, some education analysts (particularly those from conservative think tanks) have contended that the student loan crisis is “overblown.” But they’re still willing to suggest ways to address the not-problem: tying loans to specific majors, to grades, or to “student outcomes,” making loans in exchange for a cut of students’ future incomes, or privatizing the public student loan market altogether.

The Cato Institute’s Neal McCluskey argued in a Wall Street Journal op-ed that we should restrict access to student loans to those deemed “college ready.” “Dean Dad” Matt Reed weighed in in response, calling the proposal “as offensive an argument as I’ve seen in major media in a long, long time.” Sociology professor Tressie McMillan Cottom added that “privatizing access without an equal public option is absurdly racist.”

The Department of Education certainly could make it easier for borrowers to pursue deferment, income-based repayments, or loan forgiveness. Both the DoE and schools could offer better loan counseling. And perhaps bankruptcy laws could be changed so that government-issued student loans could be forgiven. (Interestingly, a judge ruled this year that bankrupt law school graduates could have their bar loans canceled.)

This isn’t simply a federal issue, of course. New Jersey, whose state student loan system has been described as “state-sanctioned loan-sharking,” does not offer any reprieve for borrowers who are unemployed, disabled, or face financial struggles – something that legislators finally decided to address.

And some colleges, particularly those serving Native American students, have abandoned the federal student loan program entirely.

There remains, instead of federal reform based on equity, a push for privatization, despite a number of scandals surrounding companies which have mishandled applications for income-based repayments and perpetrated debt-relief scams.

There’s a long list of new startups entering the private loan market, with substantial venture backing. But incumbent banks and financial companies are clearly interested in this market too, many offering refinancing and consolidation services. Goldman Sachs will now offer loans “for the little guy,” for example. And Amazon briefly partnered with Wells Fargo to offer discounted student loans – or rather, Amazon Prime Student subscribers were to be eligible for half a percentage point reduction on their interest rate for private student loans. Wells Fargo was forced to pay $4 million fine to settle a CFPB probe into its loans, and eventually the deal with Amazon was scuttled – because of “political obstacles,” according to The Wall Street Journal. (This was hardly the only scandal) Wells Fargo faced this year.)

Another new market for these sorts of loan services: marketing loans directly to companies, which are increasingly offering education benefits, including student loan aid, as a perk alongside medical insurance and 401Ks. Again, it’s worth considering how efforts like these exacerbate rather than address education inequalities.

This is the confluence of trends – from this year and onward: the privatization of the student loan market, the continued pressure by employers for employees to have some sort of credential or certification, the ongoing expansion of for-profit higher education into coding bootcamps and other short-term certification programs, the potential for a more deregulated for-profit industry under Trump. So when a publication writes a headline like this – “Could Computer Coding Academies Ease the Student Loan Crisis?” – it isn’t just Betteridge’s Law that tells us the answer is “no.” It’s history.

Rethinking Federal Financial Aid

Student loans are just one part of financial aid. But because of the increasing cost of tuition and associated living expenses, loans have become necessary for most students and their families.

There were several attempts to improve the federal financial aid program this year. President Obama called for the reinstatement of year-round Pell Grants, for example, which would allow students to receive aid dollars for summer school and ideally help students graduate faster with less debt. But the House of Representatives rejected that. Forty-four colleges will participate in a new program that extends Pell Grant eligibility to high school students in dual enrollment programs. Sixty-seven schools will participate in a pilot program that will provide Pell Grants to incarcerated students working on their college degrees. Stuck in committee: a proposal by Senators Bob Casey and Orrin Hatch to eliminate the FAFSA’s drug conviction question and prevent students convicted of drug offenses from losing their financial aid.

And then there’s EQUIP, a pilot program that will extend financial aid to “alternative providers,” including MOOCs and bootcamps. I’ll look at EQUIP and the history of the future of for-profit higher education in the next article in this series.

The Department of Education did promise to simplify the financial aid application. But the changes, including ditching the 4-digit PIN for a username and password log-in, actually made it harder for some students, particularly low-income ones, to complete the form. POLITICO reported in March that those who’d finished the form dropped by 7% from the previous year.

The New America think tank issued a plan in February to scrap the current financial aid system and re-start from scratch. Perhaps, under Trump, New America will get its wish.

One small, but noteworthy effort to rethink financial aid comes from Sara Goldrick-Rab. (Again. Read her new book.) This year, she launched “The FAST Fund,” a grassroots effort – a micro-scholarship of sorts – to meet the emergency financial needs of college students. These needs don’t always have large price tags. But the needs are immediate. And the FAST Fund reflects Goldrick-Rab’s research and a recognition that we must rethink how funding is calculated and distributed to students in need.

Textbooks (Open or Otherwise)

In previous years, I’ve carved out open educational resources into their own section, but again, I want to connect the continued high price of textbooks, as well as the false promises for a digital “fix,” to these larger conversations about college affordability. As with MOOCs and with student loans, I want to point out the political and corporate players.

If, as the Bureau of Labor Statistics has reported, tuition has increased 63% over the last decade, that’s still a much slower climb than the cost of college textbooks – up 88% over the same period. And research shows, not surprisingly, that the high cost hurts student achievement (at the K–12 and at the higher ed levels.) Students are actually spending less on textbooks, but as Mindwire Consulting’s Phil Hill observes, that’s not necessarily good news: “first-generation students spend 10 percent more, acquire 6-percent-fewer textbooks, and end up paying 17 percent more per textbook than do non-first-generation students.”

There have been efforts to push for free and openly licensed educational materials instead of expensive, proprietary textbooks for some time now; and these might be gaining momentum, in part from a boost from the Obama Administration – its #GoOpen campaign, unveiled last year, and the Open eBooks program, launched in February. The former is a Department of Education initiative encouraging schools to adopt OER; the latter, which launched with a video message from First Lady Michelle Obama as part of the administration’s ConnectEd initiative, is a partnership between the Digital Public Library of America, the New York Public Library, and First Book to offer free e-books (although, to be clear, not openly licensed e-books) to low-income children.

There have also been efforts to expand college degree programs that rely entirely on OER. Achieving the Dream, an education reform group funded by Blackboard, Cengage Learning, the College Board, the Lumina Foundation, and others, for example, announced in June an initiative develop OER-based degree programs at thirty-eight community colleges in thirteen states. “As a result of this program,” Lumen Learning’s David Wiley wrote, “by fall of 2017 somewhere between 3% and 4% of all community colleges in the US will have at least one all-OER degree program.”

Despite this and other efforts, many faculty remain skeptical about digital materials and are unfamiliar with open educational resources. Or at least, that’s what a report issued by the very objective I’m sure Independent College Bookstore Association says. TES Education, a British digital education company, says that it found teachers use OER more than they use textbooks. The Babson Survey Research Group’s survey found that just 5.3% of courses use OER. Cengage Learning claims that OER usage has the potential to triple in the next five years – that’s code for “invest! invest!” – but of course, when companies predict the future of education technology, markets are always, always expanding.

Open-Washing and Weaponized Openness

Openwashing: n., having an appearance of open-source and open-licensing for marketing purposes, while continuing proprietary practices.

— Audrey Watters (@audreywatters) March 26, 2012

This remains one of my most popular tweets, and no doubt it continues to resonate with people – four years after “The Year of the MOOC” – because “open” continues to reflect ed-tech PR more than praxis.

The giant of online retail, Amazon, entered the education technology market in June of this year with “Amazon Inspire.” The launch was first rumored earlier in the year when Education Week leaked that the company was working on an OER platform. I was skeptical then; I am skeptical now. There’s a long history of failed attempts to create OER portals and OER markets, and it’s never been clear to me that Amazon’s engineers learned from any of those.

Indeed, just one day later after its big launch, The New York Times reported that Amazon had had to remove content over copyright issues. The content in question was lifted from rival site TeachersPayTeachers. “The fact that this happened so early in the process (literally, screenshots distributed to media contained content encumbered by copyright),” Common Sense Media’s Bill FItzgerald wrote, “suggests a few things”:

At least some of the people uploading content didn’t understand the basics of copyright and/or fair use;

At least some of the members of the team uploading or creating content didn’t understand the basics of Creative Commons licenses;

The review process was either nonexistent, or not staffed by people who understand copyright, fair use, and/or Creative Commons licenses.

“I don’t see OER as a threat,” the president of McGraw-Hill’s K–12 division said in March – and that speaks volumes. Perhaps it’s that proprietary textbook companies continue to argue that openly licensed content is “inferior.” Or perhaps it’s that these companies have already integrated OER into their offerings, hoping that they can maintain customers in “free and open” as well as in “paid and proprietary.”

Yes, there was plenty of business activity this year surrounding the word “open,” much cramming as many variations of the word into the press release as possible: “OpenStax partnered with panOpen to expand OER access,” for example. And there were plenty of eyebrow-raising legal actions taken by those who’ve embraced the term – attempts to trademark a MOOC and MOOC-related certificates, along with a lawsuit by Great Minds against FedEx, contending that former’s stores are in violation of the Creative Commons non-commercial licensing of Great Minds’ materials when they charge for photocopies of its curriculum. With patents filed by Khan Academy and Coursera, two of the many organizations that have embraced “open,” it seems as though IP rights could again be wielded by ed-tech startups in order to to obtain a business edge.

So yes, “open-washing” continues to be a problem. But it’s the second part of the title final section I want to end with: “weaponized openness.”

How can those who’ve embraced the mantra of “openness” reconcile their demands for transparency with those made by an organization like Wikileaks this year, for example, which actively wielded stolen data under those very auspices during the US Presidential Election? Indeed, education analyst David Kernohan has raised a number of important questions about the similarities between the rhetoric of “open” embraced by those in open education and that promoted by the neo-reactionary factions of the technology industry.

The last thing I was expecting was that these guys were me. Us. Tonally, structurally – the same tools and tropes I’d use here to talk about education technology or whatever the hell else are used to talk about this…stuff. …If you go to any random ‘radical education technology’ conference – say, perhaps, #opened16 – none of these tropes [of neo-reactionism or tech accelerationism] would seem out of place. After I’d stopped being shocked, I started wondering why I was shocked. … They are us. They are us.

These might be uncomfortable insights for many in education technology, particularly those who do not see themselves reflected in the politics of neoliberalism or techno-libertarianism. And yet. And yet, the embrace by the technology industry – by its investors, by its entrepreneurs, by the Peter Thiels and the Marc Andreessens – of MOOCs as a neoliberal, techno-libertarian vehicle should have been a hint that there were dangerous affinities there. Blinded by its insistence on an imagined progressivism, education technology has refused to recognize its actual politics.

And as such, education technology has helped further stories about education as “free” and “open”, stories that have promoted a particular version of that very phrase: education as an expensive and privatized risk (one that's profitable for industry) rather than as an accessible, equitable public good.

This post first appeared on Hack Education on December 7, 2016. Financial data on the major corporations and investors involved in this and all the trends I cover in this series can be found on funding.hackeducation.com. Icon credits: The Noun Project